Eilat to Basata

“The Nile is Egypt and Egypt is the Nile” Practically everyone we met told us this, incanting it like a mantra. —That was ten years ago, during my first and only other trip to Egypt, which was really just a long weekend in and around Cairo. It seems that this ancient adage still applies however, even in an Egypt hundreds of miles from the Nile.

Only ten kilometers of nasty Israeli coastline separated our beds in Eilat from the Egyptian border. Propelled by a killer tailwind, we were there in two shakes of a camel’s tail. The exit process was precisely the same as the two that we had endured on our way to Jordan: lots of steps, lots of shekels to be dispensed, lots of suspicious, gun-toting teenage girls, lots of questions. We met two Italians coming the other way on a motorcycle. They informed us that the road ahead would be hilly but nicely-graded (“Yeah, if you’ve got 1000cc between your legs,” I thought) and that the Egyptian authorities would demand a bribe, plus a lot of our time. It had cost them in excess of $400 to bring their motorcycle in, they explained. Groaning, we headed toward the massive building comprising the Egyptian customs and immigration.

While the Italians had been correct about the amount of time it would take, crossing the border didn’t cost us a dime. We entered the vast, empty hall and wandered about aimlessly for a while. The place was full of uniformed immigrations and customs inspectors, but they seemed to exist in another dimension, turning their heads away from us as we approached, and looking straight through us when we asked questions regarding the procedure. It was as if we were invisible. Only the money-changing guy seemed aware of our existence, when we started giving little kicks to the non-functioning ATM machine. “There’s another one at the Hilton,” he informed us. He also pointed the way to the person in charge, a balding, rotund and self-important man who told us we couldn’t obtain a visa for Egypt here. “You mean you won’t let us across?” He shook his head and told us we could enter the Sinai without an Egyptian visa. “But I thought the Sinai was in Egypt,” I said, to which he responded with a blank look. How would we get to Luxor? I wondered. “You can get a visa in Eilat,” the man told us. But neither the thought of riding against the wind nor having evidence of my visit to Israel appealed to me. Besides, at the Egyptian embassy in Aqaba they told us we’d be able to get visas at the border. When I asked if we could get one further down the road in Sharm El Sheikh, he said he wasn’t sure. Reliable information was apparently a rare commodity in this country.

Fred and I had a brief consultation on the subject and decided to push our luck. At the very worst, we could take the boat from Nuweiba to Aqaba, an absurd idea, but feasible. Or maybe this was just a sign that we weren’t meant to go all the way to Luxor, I thought aloud, having no idea that the worst massacre in the country’s history was occurring at that very moment, in precisely the place we had chosen as our destination.

There were still many formalities to take care of, but we only discovered these when we unknowingly broke the rules. The silent, laconic border guards, for instance, flew into a frenzy when we began pushing our bikes towards the exit. In irritated pantomime, they instructed us to put all of our possessions —including the bikes— through an x-ray machine. Somewhere during this process we encountered what appeared to be the only other traveler crossing into Egypt that day. A tall, skinny Brit, he was traveling on a moped, on his way to Eritrea and points east. Later, at Basata (where there are no secrets) we learned that this eccentric person was sponsored by Honda, and had already covered absurd amounts of distance on his little scooter.

Stopping to change money at the Taba Hilton —constructed by the Israelis when they controlled the Sinai and just meters from the border— we ran into him again. He assumed we were stopping to spend the night, apparently having pegged us for the princessi that we are. No, I explained, we were pushing on, through the desert and hopefully to the Nile, to “Egypt.”

Downtown Taba materialized only a couple of minutes’ pedal further, and while it may not be the real Egypt, we definitely weren’t in Kansas anymore. The village consists of a ramshackle collection of cement structures organized around a central “square” filled with diseased-looking camels and randomly-strewn piles of garbage. It was already well past noon and we were hungry from all the strenuous immigration hassles, so we stopped at a gritty, fly-infested “café.” While a little brown boy assiduously attended to the task of grilling our chicken, we absorbed the ambiance. I thought how different this place was than Israel, and how we’d be spending the better part of the following year in the developing world. After an interminable wait, the chicken finally appeared, and it turned out to be as delicious as it was cheap. “I could get used to this,” I thought to myself as we straddled our bikes once again, heading for the open road.

Alas, one more bureaucratic hurdle remained before we could plunge into the rugged countryside. A scruffy-looking guy holding a gate said we had to pay a tax to leave Taba, forcing us to retreat to a filthy cubbyhole on the main square, where another unsavory character lurked, shaking us down for five bucks apiece.

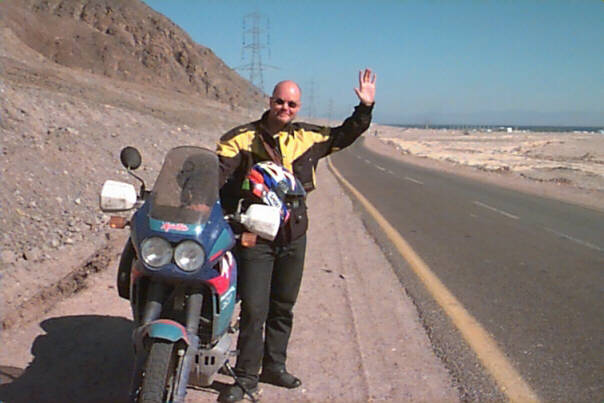

A few pushes of the pedals put Taba behind us. Multihued faces of rock rose above us on our right side, while on the left the azure Gulf of Aqaba glistened invitingly. Parts of this pristine coastline were hideously marred by giant resorts under construction. I wondered who would ever fill these places up. Most Israelis would never consider vacationing in Sinai, and visitors from the rest of the world grow increasingly allergic to Egypt with each new terrorist attack. The whole thing smelt of a Mubarekian boondoggle.

The supposedly flat road grew quite hilly. We played leapfrog with trucks for the rest of the day. They groaned slowly past us on the way up the steep slopes, and we’d scream by them on the way back down. Predictably, our tailwind had shifted 180 degrees, so even some of the downhills required straining. And the picture-perfect day had given way to brewing storm clouds.

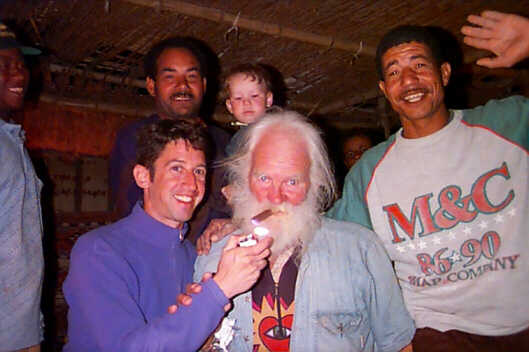

The first big drops started falling just as we arrived at a place to stay on the beach, called Basata. From the road it looked like a godforsaken rathole, a random assembly of reed shacks on a rocky shingle. But for tonight it would have to do, the only shelter for miles around. A German woman —whom we took for the manager— showed us around the place while rattling off a long list of do’s and don’ts. Other guests were milling about the main “building”, where rain was already pouring in through the reed roof, looking miserable in the gathering darkness. Checking in at the same time as us were an odd trio of hippies: a young German girl called Verena; her Israeli admirer, Yaron; and a standoffish, head-in-the-clouds American trustafarian whom we called “jingle belt” for the string of bells she had tied around her bare midriff. We guessed correctly that they had met at the rainbow gathering up the road in Ein Yehov, and that Yaron had brought them here.

“It’s the fifth hut down the beach, if you want to look at it,” our hostess explained, noting that it might be a little wet inside, but that “it never rains here, so it probably won’t last.” Our other option was to pitch our tent on the beach, which I thought would be drier. Fred’s idea was to set up the tent inside the hut, making me wonder if the ride through the desert had baked his brain.

The hut itself was very simple indeed, just a bunch of reeds (obviously imported from an area of Egypt that had plants) tied loosely together and threatening to blow away in the increasingly blustery wind, a couple of mattresses without sheets, and a blanket for a door. No electricity, no running water, not even a window. I could feel Fred’s dismay and promised we’d only spend a night here, and would reward ourselves the next day with a “princess fix” at a glam resort.

For want of activity and light, we headed back to the common hut and tried valiantly to play backgammon by the light of a single candle. Other guests —primarily brooding Israelis— lounged around and whispered conspiratorially, no doubt commenting on our inappropriateness. The place had the feeling of a meditation retreat, and we felt distinctly out of place. Dinner —served family-style at a long, low table— helped us break the ice a little. Miraculously some electric lights came on, and we warmed up to a German family through playing with their two-year-old, Phillipe. Then an Arab with dazzling green eyes and an infectious smile appeared, decked out in a jelaba and a kefiya. His name was Sherif, whom we discovered the next day to be the owner of the place. Feeling a bit like intruders in an ashram, we slunk back to our hut not long after dinner, and sat in the damp, sand-blown darkness until beset by fatigue.